Occupying Dublin: Considerations at the crossroads

Another global wave of critique and resistance would come, I told myself and anyone who asked. For many years I watched and waited. Not passively, but actively, keeping alive the social memory of movements past, analysing the ever-shifting shape of the global system and going into the streets to protest against many forms of exploitation. We no longer had the wind at our backs. Our numbers were small. Our voices were marginalised. Nevertheless we knew that the structural problems that had brought us on to the streets in the beginning had not been solved.

As boom led to bust, expropriation intensified by means we never imagined possible. The level of anger rose greatly, but activity not so much. The powerful were even more powerful and we were so powerless.

Iceland, Greece, Tunisia, Egypt, Spain, Chile, etc, etc. Would it be everywhere but here? Here being a country that had plunged down in the world far more dramatically than most. Yet we beheld signs of Greek protesters saying ‘We are not Ireland’. The shame of it. What would it take to get Irish people to act?

The trade union movement got 100,000 out on the streets of Dublin in November 2010 and everybody went home again. After beholding the indignant on the squares of the world in 2011, I thought that we had to get out and stay out.

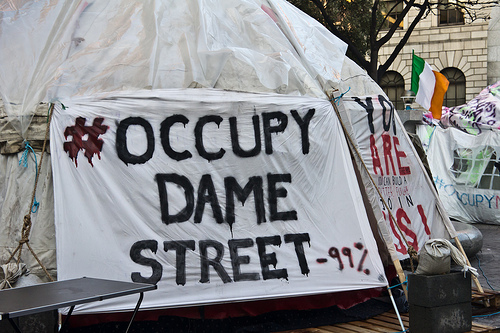

Then came Occupy Wall Street. I tweeted: “#OccupyIFSC. Up for it?” I wasn’t the only one. It was in the air. During the first week of October, it got focused. There were already several actions planned for 8 October. There were several small groups planning to be at the Central Bank in Dame Street with a street theatre flavour: one going for ‘pots and pans’ and another for ‘the shirt off our back’. Then #OccupyDublin and #OccupyDameStreet started trending on Twitter. On Facebook too we got liking and planning.

It was spreading like wildfire throughout the US and other countries and continents too. I got reports from Occupy Philadelphia, the place where my protesting began. A meeting to plan it that week attracted massive attendance, including many of my new left friends, veterans of many protests, greyer now but still going, along with many new to protest. The occupation started on 6 October and I was mesmerised by the livestream. I was fascinated by a general assembly where participants responded to the question ‘Why are we protesting?’ by telling their stories in the call-and-response of the mic check ritual.

There was a sixties feeling sweeping over me. A Buffalo Springfield song came back to me. It went “There’s something happening here. What it is ain’t exactly clear.” I found it on YouTube and posted it and it spread. It kept playing in my head. Of course, I knew there was a difference between the 60s and my 60s, but I was determined to be up for it.

All week I was on the social networks stirring it up. I do not believe in the idea of Facebook or Twitter revolutions, because the impetus comes from real social conditions and relations, but these technologies and networks greatly enhance the capacity to connect and to build social movements. I am especially aware of it for having organised for so many years before they existed.

I put everything else on hold. I stopped writing a book in mid-chapter. This book is an attempt to synthesise autobiography with intellectual and social history. It would not do to stay home and write about struggles of the past as a reason for not engaging with the struggles of the present. This was still my time. My position as a professor emerita gave me a certain freedom of time and movement.

I met with a number of people planning for Occupy Dublin/Occupy Dame Street to start on 8 October as well as for the international day of solidarity on 15 October at Seomra Spraoi, an autonomous social centre in Dublin city centre. It reminded me of many spaces of the sixties. I met people I had been interacting with on Facebook and Twitter, but had never met face-to-face. I saw a lot of them in the coming days. This was the weekly assembly of Real Democracy Now, a group that had formed out the 15-M movement in Spain. They had asked me to speak at the event they were planning for 15 October. Those who had put the #OccupyDameStreet hashtag on Twitter and set up the Occupy Dame Street Facebook page were there, looking to RDN as experienced organisers, as they had been in the field for a few months already.

On 7 October, the US embassy in Dublin warned US citizens to avoid the area around Dame Street, because of anti-financial sector protests. I posted this to Facebook, which led to some discussion of a paranoid nature. I revealed that the US embassy was following me on Twitter. It meant that we were getting the word out there, which was what we wanted to do. At the same time, we wanted to project it as a peaceful communal gathering to address what was happening in the world and not a skirmish between testosterone-charged hoodies and cops.

On 8 October, I woke up with a great sense of excitement, not knowing quite what to expect, but hoping for a new momentum in our political scene. I arrived at the plaza in front of the Central Bank on Dame Street just after 2pm. There were many people I had never seen before, along with ones I met during the week and a few I knew for many years. Most people did not know each other. There were 300 or so. I look back on that day with fondness, because the atmosphere was so fresh and open, because all voices were equal, because there was such hope in the air.

I suggested that we use the mic check idea, as I had been so moved by watching it in Philadelphia via livestream. One by one people came forward. It was a powerful ritual, reinforcing attention and building cohesion. We told our stories and said why we were angry and why we weren’t going to take it anymore. We served notice that we were organising to take back the world that had been taken away from us. There were also conversations, one-to-one or in small groups. There was a sense of vital bonds being forged.

After seven hours, I went home and slept in my own bed. I didn’t camp overnight, as I didn’t think it appropriate to my age. I had done so in my youth, especially in 1971, where we created a massive encampment in Washington DC as a base for mass civil disobedience in response to the continuing war in Vietnam. As soon as I got in the door, I tuned in to the livestream of Occupy Philadelphia, where there was a march from City Hall to Independence Hall. A young black girl was speaking, while the assembled repeated her words. “I am homeless. I am homeless. I am hungry. I am hungry. My grandmother is sick and can’t afford health care …” It was powerful. Resistance had stepped up its tempo.

I returned on day two, a Sunday, which was a much quieter day. I participated in a smaller assembly and found it really frustrating. It was about defining what we were. Over and over in the next days, I heard things that made me cringe at the conceptual confusion that seemed to prevail: assertions that this was not a political movement, that it was neither right nor left, that participants were welcome as individuals, but had to leave their politics at the door. I tried to be patient, to argue that a person’s political philosophy was something integral to his/her being and not something that could be left at the door, aside from the other absurdity of this constant injunction - the fact that we had no door! I invoked a conception of politics that was broader and deeper than party politics. We need to reclaim the polis, I contended. Some took the point, but others continued with the ‘no politics’ rhetoric regardless.

There was also a problem, especially when speaking to the media, about when a person could say ‘we believe’ as opposed to ‘I believe’. ‘I, the people’, one tweeter wryly remarked. There were many personal opinions put forward as collective expressions, which I found really objectionable, especially the declarations of ‘no politics here’. Someone from the Workers Party came along with some copies of the latest issue of Look Left, an attractive, intelligent, broad left magazine, to contribute to the library and was told ‘no politics here’. However they were eventually accepted and hopefully read.

I understood and accepted the determination to create a movement with no affiliation to political parties and to resist entryism on the part of any existing political formations. However, discussions were dominated by an unhealthy emphasis on who/what to keep out rather than who/how to bring in support for this movement. There was an obsession with a ban on political and trade union banners and literature. There was fear of any organisation bringing its own agenda into this movement. In fact, Real Democracy Now brought its participants and its agenda into the occupy movement in an entirely natural way. They involved themselves in all aspects of the occupation in a way that was hard working, enthusiastic and constructive. Another political grouping was the Workers Solidarity Movement, an anarchist group, whose members participated in an organic and constructive way, which no one found problematic.

From the beginning, in fact before the occupation actually started, much of such discussion was driven by hostility to the Socialist Workers Party. The immediate cause was that the SWP-driven Enough campaign had changed the date of their planned anti-IMF-ECB-EC march from 8 to 15 October because of a change in the date of the troika visit, and then asserted that their march was the Irish event in the international day of solidarity, whereas RDN had been organising to be the Irish event for that day for several months. Others involved in the occupation had some previous experience with the SWP and accused them of dominating broad organisations by monopolising membership lists and aggressively recruiting. These specific changes escalated to a way of talking about them as if they were sinister and evil, rather than being another force on the scene that was mobilising on the same issues. Any attempt by the SWP to relate to the occupation was seen as an attempt at infiltration. Perhaps if they had involved themselves more organically from the beginning and contributed to the camp and working groups, instead of coming along to assemblies when they wanted to argue specific positions, it might have been better, but then again it might also have increased the charges of infiltration. Some of those who became most hostile to the SWP had to ask initially, ‘What is the SWP?’

In the first week of the occupation, the working groups began to form. Eventually there were groups for food, security, construction, facilitation, solutions, outreach, media, talks and events. With every passing day, things became more organised and our lives moved to a new rhythm. There was a flurry of activity, especially on the plaza and the social networks. The times they are a changin’ rang out in the night air. I loved the presence of this powerful song from my past in this present scenario. The music on the street during these months was one of the best things about the occupation. Christy Moore, Damien Dempsey, Liam Ó Maonlaí, Glen Hansard and many others sang at the site.

On day three, I went from ODS to the Mansion House for a memorial for Kader Asmal, who had lived and been active on the left in Ireland for many years before returning to South Africa, where he became a government minister. I felt an odd sense of dissonance in moving from one milieu to the other, where I was mixing with the next president of the nation, the mayor of the city, a minister in the government, some academics, even several Central Bank economists. ODS was barely a blip on their radar. Most all of them were left of centre, looking back in comfort at a spell of activism in the anti-apartheid movement of the past. When asked what I was doing these days, I mentioned ODS. Some showed an indulgent, but distant, interest, while others couldn’t get away from me fast enough.

From day two on, the weight of my efforts went into organising a series of sixties-style teach-ins. We called it Occupy University. I hoped it would help to bring theoretical clarity and historical perspective to this project. We had two or three talks a day, all out in the open air on Dame Street, except in the heaviest rain, when we found nearby indoor venues. There was something bracing about doing it on the street and struggling with big ideas in the midst of the noise of the buses, ambulances and fire engines and the interruptions of attention-seeking alcoholics and drug addicts. We also got passers-by, who stopped to listen and stayed to talk, while others tarried only long enough to tell us that we were wasting our time. We invited them to feel free to participate, but not to disrupt.

Many of our talks were about the global financial system: hedge schools versus hedge funds. We also concentrated on talks about previous social movements, as well as branching out to ideology and culture. We also had workshops on practical matters: writing, media, music, direct action. Those attending were of different ages, genders, races, occupations and, most importantly, different educational levels. There were professors and doctoral students along with people who had left school at an early age. Most speakers pitched their talks well to encompass this diversity. Speakers were academics, journalists, politicians, poets, bloggers, trade union officials, alternative media practitioners. Sometimes discussions stayed reasonably well focused and sometimes they went all over the place. There were conspiracy theorists and currency crazies and fluoride fanatics, who used the discussion of anyone else’s talk as a platform to give their own talks. Mostly there was sincere sharing of knowledge and earnest interaction, pursued with a purity of purpose, all too absent in academe. In two months we organised 78 talks and workshops.

Sometimes we got so fired up about the nature of the whole global financial system and the revelation of local details of how flagrantly we were being robbed that we could hardly stand it. The Sunday morning when we listened and questioned blogger David Malone, while sheltering from the rain under the structure of the Central Bank, was revealing, unbearable, poignant and funny all at once. Sometimes lecturers were asked questions that stopped them in their tracks. Andy Storey gave a lecture on the IMF and asserted that there had been zero rise in GDP in African countries ‘assisted’ by IMF programmes. An earnest young man was astounded and asked ‘What? Even with Live Aid?’ Actually he spoke for many Irish people, who believe that Bono and Bob had basically sorted out Africa. Sometimes people suggested measures to reform capitalism, such as a transaction tax, while other times people tried to imagine a future without capitalism. There was a lot of debate on the crisis in the eurozone. Terrence Mc Donough, professor of economics in Galway, made the strongest case for exiting the euro, whereas other economists cast doubt on this as a strategy.

Our system for booking talks was ad hoc, really rough and ready, but it worked. At least it worked until we had a minor crisis. At first the problem was being too tightly circumscribed. When I proposed a series of talks at the assembly on day three, everyone was all for giving us the go ahead. When I started elaborating further on topics and speakers and mentioned that Michael Taft was a trade union economist, the anti-trade-union reflex was triggered. Then one person, who was very assertive in week one and disappeared thereafter, suggested that we come back when we had the list more complete. It was looking as if every topic and every speaker would be argued at every assembly. I did not think that would be viable. It was logistically too awkward. A few days later we brought it up at an assembly again under the name of Occupy University and agreed to operate it autonomously. We set up a Facebook conversation as our mode of meeting, supplemented by texting to the site. I contacted radical academics, journalists and writers, whom I knew, as did a few others. Sometimes somebody appeared at the camp with a proposal or contacted us through the website. Not only was ODS a necessary venue for progressive tourists to visit and musicians to play, but an OU talk was the same for visiting progressive intellectuals, such as Patrick Bond and Michael Albert. Others who spoke included Fintan O’Toole, Siobhan O’Donoghue, Harry Browne, Gavan Titley, and Conor McCabe. The full list of speakers and topics is here.

We never discussed criteria for speakers, because we assumed common understanding of the project. Until the name of Eamon Ryan appeared on our timetable. He was now leader of the Green Party, but had been a government minister, defeated in the election earlier in the year. He was a particularly arrogant exponent of the decisions that brought us to our knees. I was told that he would speak on ‘energy, no politics’, which I did not find acceptable. I introduced the session in a civil but less than welcoming way, asking participants to let him have his say, but indicating that all should be able to address the politics of energy as well as to air their grievances with the last government. The discussion veered from people losing their tempers at his very presence and walking away to engaging him in ideological debate to being honoured by his presence and trying to impress him. I was astounded at the latter, especially because I had been careful not to invite Richard Boyd Barrett of the SWP, who had been elected to Dáil Eireann in the recent election, or Alex Callincos, when he was in town for the marxism conference, as I thought it would inflame the situation at this stage. People who didn’t want to be tainted by association with trade unions and left parties were gushing over a politician who voted for and justified what ODS was set up to protest.

We did invite academics, such as Marnie Holborow and Sinead Kennedy. We had a media workshop, given by Paula Geraghty, and a poetry anti-slam, organised by Dave Lordan, who also performed ‘Living with the recession’. These were all well received, taken at face value, by participants who were unaware of their connection to the SWP. Paul Murphy MEP of the Socialist Party spoke at OU as well as an assembly. He wrote an article on Politico.ie taking a constructive approach to the occupy movement. Most received him well, although one wrote of left politicians having ‘wet dreams of left unity’ because of the occupy movement.

Trade union officials tended to get a rough ride. When Mick O’Reilly spoke, a woman screeched at him demanding that he call a general strike immediately. When Sam Nolan gave a sketch of the history of trade unions in Ireland, it was our longest session, with many people coming and going. After several hours and darkness falling, a new wave of participants were asking questions that had been asked and answered two hours before that. One young woman ranted against trade unions from a position of utter ignorance.

I gave a talk myself the first week on the new left: remembering and reflecting. I told the story of the 1960s-1970s new left as it unfolded and as I experienced it, focusing on themes relevant to this new movement: redefining the political, naming the system, problems of leaderlessness, forms of resistance, prefigurative politics, relations of old left and new left, participatory democracy. When I used the phrase ‘participatory democracy’ in connection with the Port Huron Statement of 1962, I could see a look of shock on a few young faces, who thought it had just come into being with this movement.

I tried not to be an old know-it-all, who had been-there-done-that, but so many things being said and done did remind me of so much that had been said and done in the past and I did find myself saying so. At the same time, I did know that this historical conjuncture was unique. I felt that I had something specific to offer as a voice connecting past and present; as someone who could tell this story within the framework of a longer story.

The Occupy movement is clearly part of a narrative of the left, but it is broader than that. It encompasses elements who do not consider themselves left. The spectrum is wide, but tilted way to the left. The political philosophies most clearly in evidence are social democracy, marxism and anarchism. Among those giving talks, marxism has been the strongest presence, although not in a doctrinaire, or even heavily sign-posted, way. Among those most actively seeking to form and articulate their political philosophies, particularly under the stimulus of new activism, anarchism seems best to catch their mood and to impel them to develop further. Moira Murphy, the events organiser, decided that she was an anarcho-marxist.

The issue of demands has been a contentious one, particularly at OWS, although not so much at ODS. During the first week, there were four main demands formulated. These were: (1) an end to IMF/ECB control of the Irish economy; (2) repudiation of private bank debt that had been socialised; (3) national control over our oil and gas reserves; (4) participatory democracy. Elsewhere in the Occupy movement there was reluctance to make demands, as demands imply acceptance of a system that the movement has set out to undermine or even overthrow. These were broad demands on which everyone could agree, but could not easily be conceded.

There was a dialectic between reform and revolution in play and a whole spectrum of positions on what the relation should be. Some came out of anger at ‘corporate greed’, which is not the same as a critique of capitalism, but for many it could be a step along the way to it. While the basic thrust of the movement was in the direction of a systemic critique of capitalism, there were some, here as elsewhere, who would be satisfied with a reformed capitalism and a return to national economic sovereignty. For those who were seeking more, the nature of the imagined alternative was clearly socialism for some, but something uncertain for many others. There were some who advocated a return to barter and brehon law. The milieu was one where we could discuss alternative visions without having to come to agreement on a detailed programme or even a common political philosophy.

We had our first march on 15 October, the day of international solidarity. The ODS march fused with the RDN one already planned for that day. There was great sense of being part of a global wave. There were occupations in nearly 1000 cities in 82 countries on 6 continents at that stage. Despite the complication of the Enough march, many people attended both and numbers were good (about 2000) and spirits were high. When we arrived at Dame Street, I spoke at the beginning of the assembly, as I had previously been asked to speak by RDN. I tried to combine reflection with rabble rousing, but the rabble needed little rousing. They were in fighting form. While recognising that this movement was about occupations and demands, I warned against reducing it to occupations and demands, especially against believing that this occupation in itself would lead to achievement of these demands. I argued that we needed to build a movement to engage in a complex, protracted and difficult struggle. I stressed that we were up against the most formidable force in the whole history of the world and that we did not really know how to unravel the structures of political and economic power that made it possible for the 1% to rule at the expense of the 99%. In other words, marxist words, how to expropriate the expropriators. We do not really know how to do that now, which was a reason why we had to make the Occupy movement a site of study as well as a site of struggle. This was published in Irish Left Review.

The structures and rituals of the project came into shape: the camp, general assemblies, working groups, teach-ins, marches, musical and poetic performances, direct actions, conversations. Sometimes it all fell together in wondrous harmony, but discordant notes could be detected. There were problems at the core of the project that were bound to erupt into full-scale conflict, as they duly did.

One of these was the tension between camp and movement. From day two I felt that those who were free to camp had a disproportionate voice in defining and deciding what the movement would be. I wanted this to be a movement of those with jobs, kids, complications; lives that made it impossible to camp, but could find ways to participate according to their situations. Understandably it was those who were camping, many of whom were unemployed, who were available to do the media interviews, who could attend the general assemblies at 1pm and 6pm every day. At an early stage, there were no agendas available in advance and no minutes to check afterwards. Although I was there almost every day for 3 to 7 hours a day, I was not present when crucial decisions were made, such as the ban on party political and trade union banners and literature from the site as well as from all marches and activities of ODS on other sites. It was by no means obvious that trade unions and left parties wanted to rush in to be part of this and to bring their banners on our marches. The contradiction between the declarations of inclusiveness and practices of exclusiveness would continue and accentuate to the point of absurdity.

There were bound to be problems basing a movement in a camp, but there were also pluses. It was symbolically powerful to occupy a public space, especially there in the city centre, as a challenge to the system visible 24/7; as a 24/7 point of contact for people to come to participate in opposition to it.

It was not only about opposition. It was about forming new bonds of solidarity and experimenting in participatory democracy. It was about giving and receiving food, shelter, culture, knowledge and labour, liberated from the circuitry of commodification. There was a strong sense of prefigurative politics, of building the new in the shell of the old, of being the change we wanted to see in the world. There were times when the plaza was alive with this sense of an alternative space. There was such a buzz to all that talk, music and activity on the street.

I was full of zeal for this idea in my new left days and subsequently saw our counterculture ebb away, but it left its mark, not only on me, but on the wider culture. I still believe in this approach in my older (and hopefully wiser) way. This determination to make the means compatible with the ends, which is important, also carries the danger of becoming obsessed with the means to the neglect of the ends. This made us turn in on our own identities, our own process, our own collectives, in the past in a way that sometimes diverted our energies or even subverted efforts to build a wider movement.

Some of those camping became obsessed with the camp and with an inflated image of themselves as the core of this movement. “I camp therefore I am” I said of them on one occasion, when I was frustrated by the camp narcissism, paraphrasing Descartes to ends he never intended. One habitually referred to himself and others in the camp as ‘heroes of the revolution’. He constantly posted self-glorifying (and unattributed) quotations on facebook about how a few people could change the world and hit back at anyone who did not give unconditional support as enemies. Some resented those who came for the talks and assemblies, but did not camp, questioning their right to have a say at assemblies. Some even resented those who were in working groups, who did much of the work of the movement and were around for long hours during the day, either at the camp itself or doing organising work elsewhere. On two occasions, Occupy University talks were interrupted to demand that those attending wash dishes or move tarps, although there were others hanging around who were available. I took it as an act of hostility and lost my temper the second time it happened. Some in the camp never attended talks and rarely attended assemblies and seemed vexed at them even happening. At the same time they felt free to come and to block when they got wind of proposals not to their liking and said to people, who worked and came consistently to assemblies, that they should camp if they wanted to be part of this movement and have their say.

From their point of view, they were outside in the cold, the rain and the dark when others were home asleep in their warm beds. They were vulnerable to the drunks, junkies, thieves and crazies on the city streets when others were secure in their homes. They were up all night on security duty while others arrived after a good night’s sleep seeking interesting company and intellectual conversation. Money, laptops, mobile phones were stolen. Inappropriate sexual conduct had to be addressed. Knives were pulled. People got on each other’s nerves. As with most occupations, the homeless came and found a higher standard of food, shelter, security and community than was their norm. At the same time, people often become homeless because of other problems, problems which a political encampment was not always equipped to solve or even cope.

I respected their efforts to stay there in difficult material conditions, especially those who got on with it and remembered the political purpose of it, but I found it hard to take the guilt tripping attitude of some of those who camped to those who didn’t camp. At one assembly I asked: ‘Do you want to build a camp or do you want to build a movement?’ I believed that a camp obsession, even narcissism, was subverting the attempt to build a movement. What kind of movement could it be if it repelled people who work, people with obligations and problems that prevent them from camping? It had to be movement open to people to contribute as they were able. It had to be a movement that those people could be part of defining. Division of labour was bound to be a fraught issue and it impacted on all the working groups and other aspects of the project. Allowing for life situations and resulting availability, I was astonished at how much some people with complicated lives gave to the effort and disappointed at how little others with fewer complications stepped up to do.

The assertion of the priority of the camp put people off. Some went away. I was tempted to do so, but stayed, even if I was often angry and alienated. I sometimes found myself speaking of ODS as ‘they’ rather than ‘we’, but I still struggled to say ‘we’. Even if I wasn’t camping, I had made a drastic change in the rhythm of my life. It was a 24/7 project and I gave myself to it fully. Even when I was home, I was at the computer giving an account of it, trying to raise support for it, finding out what was going on globally. It was always in my head. When I went to sleep at night, I was dreaming about it. It seemed the biggest thing that was happening in the world in the way of resistance to the terrible forces ranged against us. Despite being obsessively orderly, I let housework go. I found it difficult to keep up with my e-mail. I stayed up far later at night than was my habit, but got up at the early hour as was my custom. I was stressed, exhausted and irritable at times.

There were ongoing tensions about trade unions and political parties, specifically those of the left. Things that were said made me furious. Basically there was a vociferous element who declared over and over that left parties and trade unions had failed. The most insistent on this were the most ignorant of the history of the left and labour movement. It was as if 8 October 2011 was day zero. One young woman, in response to a lecture on trade unions given by a political and union activist of many years, said that the unions and parties should disband and come here. This was the reality now. They did not have the vocabulary of vanguardism, but they had the mentality on overdrive. On the day of the celebration marking four weeks of the occupation, I updated on Facebook: ‘After an overdose of people pronouncing on all efforts of the past as having “failed” and proclaiming a month’s encampment as “the revolution”, I’m going to pay my respects to the efforts of the past today, while still trying to play a role in the present. I’ll be attending a celebration of the 90th anniversary of the Communist Party of Ireland and then a celebration of 4 weeks of Occupy Dame Street. 90 years. 4 weeks. Let’s have some perspective, people.’

‘Why keep doing the same things that have been tried and failed?’ they asked, so knowingly. I reacted to this on many levels. On one level, I objected to such crude criteria of success and failure. Yes, you could say that the left failed, because we still have capitalism, a capitalism that exploits more effectively than ever, but how much worse would it have been if there had been no resistance, no enunciation of an alternative? I had made the history of the left part of me and I thought of those who lived and died for this movement. I believed that they had brought illumination and solidarity to bear upon the world and I could not write off their lives as failures. Some who said this were so full of themselves in their first flush of activism and so ignorant and arrogant about all that went before them. The lack of historical consciousness was stunning. Do you know, I asked on Facebook, that there was a wave of occupations throughout Ireland many years ago, drawing strength from a powerful global movement? They were called soviets. So much they did not know. I found their lack of respect for anything that came before them offensive. I kept trying to get across to them that 2011 was not year zero.

At the same time I knew that we could not just go on as before. How many times had we gathered at Parnell Square and marched down O’Connell Street for this and against that and ended up at the GPO or Dail Eireann or wherever? Were existing socialist or social democratic parties adequate vehicles for the sort of activism appropriate to today? At Occupy Dame Street, I presented myself from day one as old left looking for a new way. I had been a member of the Official Sinn Fein (which became the Workers Party), the Communist Party and the Labour Party. However, even as someone who knows these histories and feels a part of these traditions, I find that I no longer fit into any of the existing parties of the left. I am between the old and the new. I am not part of any entryist project to recruit new people to these parties, but I have tried to persuade them to respect what preceded them and to see themselves within a larger project and a longer story.

At the same time I would like to see this story move now in a new direction and I see the Occupy movement as opening a new path. This is a new movement that cannot be fit into any of the old moulds, particularly those of vanguardist parties. I have been conscious for some time of the existence of an unaffiliated left and felt the need of the sort of movement that would gather these energies into effective analyses and activities. Most of these people have come to support the Occupy movement, at least initially, whether it is to like on Facebook or to give it their every waking moment. It has been a gathering place for these people to find each other, to discuss histories, sensibilities, ideas, plans. Occupy Dame Street has opened new spaces, literally as well as metaphorically. It has transformed the terrain physically, but also politically. It has created a new force on scene. It was not an entirely cohesive force, but it seemed to be a promising one.

The lack of cohesion played itself out particularly in a number of acrimonious assemblies. From the beginning the very mention of trade unions triggered negativity from some elements. Partly this came from a perception that the trade union movement had let the working people down. They had become incorporated in a social partnership process that had left them bereft when shut out of it by government and employers. Trade union officials had lost the skills of class struggle appropriate to the current crisis. Almost everyone coming to ODS agreed with this. However, for some it went beyond this. Speaker after speaker distinguished between the trade union leadership and its members, who needed the trade union movement to serve their needs, but certain elements wanted nothing to do with trade unions. On day three, I delivered and read out to the assembly a statement of support from the Dublin Council of Trade Unions. Those who knew explained to the others that the DCTU had a more radical history than the ICTU (Irish Congress of Trade Unions). Some days later there was another discussion of whether to allow trade unions banners on ODS marches, generating much negativity. The negativity toward trade unions was in almost direct proportion to a lack of experience of them, mainly from students and unemployed youth. Speeches were made for and against trade unions and the proposal failed to achieve consensus.

The next day was our second march. There was great atmosphere at it with singing, dancing, chanting and conversing. RTÉ even put it on the tv news, estimating 2000 on it. Billy Bragg sang when we got to Occupy Dame Street. He bridged the gap between the old and the new powerfully. He sang a few songs about banks and plutocrats, catching the mood of this new movement, and then articulated the need to get the support of organised labour and to honour the struggles of the past. He then sang Power of the Union and the Internationale. It felt great to clench the fist and to sing these songs here and now, ritualising the connection between struggles past and present, between here and everywhere. It was also somewhat healing after the divisive discussion of unions of the night before.

The next day was our second march. There was great atmosphere at it with singing, dancing, chanting and conversing. RTÉ even put it on the tv news, estimating 2000 on it. Billy Bragg sang when we got to Occupy Dame Street. He bridged the gap between the old and the new powerfully. He sang a few songs about banks and plutocrats, catching the mood of this new movement, and then articulated the need to get the support of organised labour and to honour the struggles of the past. He then sang Power of the Union and the Internationale. It felt great to clench the fist and to sing these songs here and now, ritualising the connection between struggles past and present, between here and everywhere. It was also somewhat healing after the divisive discussion of unions of the night before.

Not long after, the DCTU sent an invitation to ODS to participate in pre-budget march it was planning for 26 November. ODS was also asked to participate in the planning of this march and an ongoing campaign against austerity, and to provide a speaker at the march. It was discussed at assembly after assembly. When it finally came to a decision, it was blocked, although the majority of people who are part of ODS supported the proposal in one way or another. This was a veto, dictatorship of minority, many said. Even the most ardent exponents of consensus were among the critics. It was a misuse of the blocking mechanism, they claimed. This has been the most contested decision and it has left bitterness in its wake. A number of people who had been attending assemblies disappeared at this stage.

By this time, there was much evidence of a healthy and progressive relationship between the Occupy movement in the US and organised labour. They sang Solidarity Forever and actually enacted many forms of concrete solidarity, from giving material assistance to marching together to blockading ports. Many occupations even had special working groups to reach out to organised labour. Many speakers at ODS assemblies invoked this, but to no avail. The blockers wanted to keep their project pure.

They did not need the left or the unions. They did not seem to need those who came to assemblies or those in working groups either. They had ‘the people’. A mystified sense of the people was invoked against anyone who criticised. The people who passed by and said ‘good for you’ (and maybe did no more) were set against the activists. The people would somehow do what was required (whatever that may be) when the time came. The campers would somehow make it all happen.

The minutes of the general assembly said that, while ODS would not support the march, members of ODS were free to do so. Aside from the ambiguity of what it might mean to be a ‘member’ of ODS, no one needed ODS to be free to support this march. Some who supported the march, not only attended the march, but set up a group of ODS participants to help organise the march. It was not a democratic centralist organisation after all. Eamonn Crudden, a dynamo of an organiser, pulled together music, posters, leaflets bridging the sensibilities of the occupy and trade union movements. One demand put forward at an assembly discussing the march was that DCTU stand down their banners when they got to Trinity College out of respect for the area around Dame Street as a banner free zone. This was published in minutes and came in for special scorn on Twitter. Such astonishing arrogance. The other occupations in Ireland - those in Belfast, Galway, Cork, Waterford and Limerick - supported the march. After marching, they came to Occupy Dame Street, where there was an assembly of all the occupations. It was an occasion for rallying and singing and celebrating solidarity. I was there, but did not speak on the day. The ODS decision on DCTU was a big breach in the sort of solidarity appropriate to the moment. It was the elephant on the plaza.

Another landmark assembly was one in October that concerned a proposal from the Enough campaign to have one joint action with ODS. The SWP came out in numbers that were greater than would be usual at an ODS assembly. This has been the primary evidence cited in charges of SWP attempts to infiltrate ODS. At the assemblies and on the social networks in the days following it there were ugly exchanges, accusations of parasitism and sectarianism, the worst of them coming from the ODS side. I saw it as a positive initiative that would heal the rift created by the rival marches on the international day of solidarity. In terms of process, it was one of the worst I have ever witnessed. The facilitator (in good faith) insisted that, after the proposal was stated, only concerns could be expressed and then amendments to address those concerns. This had the effect of privileging negativity. It meant that for over an hour, only objections to the proposal could be expressed. Some speakers spoke over and over, expressing ugly accusations, before a single positive word was allowed. I objected to this procedure several times before I was permitted to speak in favour. I was one of the few non-members of SWP to do so. The proposal was blocked. I stayed around talking to those who had blocked it.

The next day, 29 October, was our third march. The atmosphere at it was terrible. In our pre-march assembly at Parnell Square, a speaker from the Enough campaign was booed. At Dame Street, there were further nasty scenes where members of Enough / SWP were targeted. This sectarian behaviour, combined with the ignorant and negative attitudes to the trade unions and left parties, made me want to walk away from ODS. Some did walk away. I persisted, but with more difficulty and less enthusiasm. I had a sense of something with great potential unravelling. I tried to carry on and to find a way to harness the positive energies brought into play. At times I was only hanging on by a thread. By 29 October there were approximately 2300 occupations in approximately 2000 cities around the world. I didn’t want to leave this movement to those who didn’t know what they were doing or did know and were doing it for reactionary reasons.

Oddly enough, there was a de facto joint action during the following week. There was a demonstration at the Department of Finance against the payment of an unsecured bond for one billion dollars. Present were ODS along with Enough/SWP and Repudiate the Debt/CPI. So were the media. I moved between the different groups, all the time worrying that there would be unedifying confrontation. As it turned out, it was an edifying example of left unity. Speakers were evenly divided among the different groups, happening organically using the open mic format. Our numbers were small, but communists, trotskyists, anarchists and undefined all kept focused on what we were protesting against and who was on the same side in doing so. It was ironic that ODS never had any problem with the Repudiate the Debt campaign, which had the same relationship to the CPI that the Enough campaign had to the SWP. Yet the fact that the SWP was the force behind the Enough campaign was made as an accusation, as if it were the worst kind of treachery.

In mid-November, I spoke at the annual marxism conference organised by the SWP on a panel on the occupy movement. There were participants in occupations of Belfast, Cork, Galway and Waterford there. They reported no major problems in attitudes to the left and unions.

It’s not even as if ODS was consistent about acting with other groups or clear about criteria for deciding. There was a ODS contingent with an ODS banner on a big student demonstration organised by the Union of Students of Ireland. This was never discussed at a general assembly. It was just done. I was for it, but noted the contradiction. How was acting with USI unproblematic, but DCTU so problematic? As it turned out, the USI stewards and the gardaí blocked the ODS and FEE (Free Education for Everyone) from rejoining the protest after a breakaway action. I was not on that march, deciding to leave that one to another generation.

The generational issue raised itself in my mind as I tried to address my problems in persisting. I noticed that a number of my new left contemporaries in the US were writing about this movement as ‘them’, analysing what ‘they’ were doing, thinking, saying. They supported the movement. They visited the occupations. They spoke at the teach-ins. They marched. But they saw it as essentially the movement of another generation. Perhaps they were right, I thought. Sometimes I felt as if I had wandered into a crèche and I was supposed to pretend to be one of the kids. Perhaps I should see ODS as ‘they’ and give my judgement on it from a generational distance. Moreover, so many of my contemporaries from my years in the Irish left also seemed to believe that it was time to leave activism to another generation.

However, it seemed to me that this was and should be a movement of all ages, even it was the first experience of activism for many of another generation. It made it too easy to dismiss it as a movement of those who were too inexperienced in the ways of the world to know how futile it was.

Even though the new left was more of a youth movement than the occupy movement is, the old left was still there. I have reminded myself of my new left attitude to the old left. It was sometimes ignorant and arrogant. I later became part of the old left and learned to know and respect what had gone before me. Others had to find their own way. It was perhaps my penance to have inflicted on me some of what I had inflicted on others long ago. Actually some of the younger people, with whom I worked, were impressively mature.

It wasn’t only the generational issue that made me wonder about my modus operandi. There was also the perennial tension of the activist intellectual between the time spent on the street and at meetings and the time needed to read, think and write about it all. I had often overbalanced towards activism and didn’t write what I should have written. I needed to rebalance. After the first month, we expanded the working group for OU and more people became involved in the work. I stopped going to ODS every day, but still went often and remained active in organising and facilitating talks, attending marches and general assemblies. I used the time to try to keep up with the global movement, which had become difficult in the early weeks of intense involvement in the local movement.

At times I had a sense of life cascading so rapidly that it was hard to process it all. One day I wrote that in an e-mail. Within five minutes, I received a call telling me that a colleague had been found dead and a minute later I heard news on radio that Gaddafi had been captured and executed. I did not mourn Gaddafi, but had been following events in Libya with intense interest, since I had been in Tripoli at the outbreak of the uprising. Every day on the news there was so much to take in, from the ongoing hegemony of the markets over states, the crisis of the Eurozone, obscene salaries at the top and more cuts to the wages and services of those struggling from below for the basics of life. However, the news of a global movement fighting back was a constant counterweight to all of the terrible news.

How to conceptualise it all? How to assess our impact? I bear the marks of many defeats and could not be so sanguine about what our movement could achieve as many of my younger comrades. Not that we used the term ‘comrades’ at ODS. It was normally ‘peeps’. I look at the world and see so much power and wealth amassed against us. I have seen so many, whom I once considered comrades, so overwhelmed by the realities of this power and wealth that they have more or less changed sides. Currently in Ireland I see those, once in the Workers Party or Labour Left, with whom I once stood, now in government, standing against us, instruments of the global elite, in our lives here. I am standing up against this power and wealth, no longer because I feel confident that we can prevail against it. I keep doing it only so as that they cannot rule uncontested. I do believe that another world is possible, but the odds seem to have mounted as the years have passed.

The young do not tend to see it this way. They are in their first flush of activism and they feel the wind at their backs. They think that somehow they will prevail. They don’t quite know how, but they have a sense of their own power and they are high on it. I remember that. I wish that I could still believe in that way, but the years have taught me to assess the balance of forces such as the evidence demands, accustomed as I have become to seeing history unfold disdainful of my desires. I have often invoked Gramsci to myself: pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. Optimism of the intellect was much in evidence at ODS. Many of the inspirational quotes posted physically at the site or electronically on Facebook indicated that you could make happen anything you want to happen if you are determined enough. Not so. A hard lesson learned the hard way.

Actually most of the young people with whom I worked learned a lot in a very short time, in the way that you do in the crucible of practice. They too were critical of the lack of historical consciousness being articulated and were keen to enhance their own knowledge of history, especially the history of the left. Their political judgement was sometimes more astute than some older participants. There were different mentalities that were not reducible to generational patterns.

Both old and young experienced exhilaration, exhaustion, disappointment and revival on the roller coaster ride of the autumn. There was a need to take stock as winter came and numbers declined. What did we have to show for it all? Despite all the negativity, something had been achieved. We stood against those who oppress us and we found each other. Many who had been looking around for a way to act, coming along to an occasional protest, but not really fitting into any existing organisations, came together through the Occupy movement and will not retreat. We know each other now. We have shared our stories. We have worked together productively. We have experienced the world in a new way standing together in this new space. Even though we have become alienated from what we have created, we can find another way forward.

The media coverage, although relatively benign, was not in proportion to what the occupation deserved, especially in the early weeks when there was so much activity at ODS. In contrast, the presidential election, which did not deal with any of the real issues facing us, was given saturation coverage. Still RTÉ, TV3 and Al Jazeera broadcast from the site, as well as reporting it and having participants on studio panels. Many of the newspaper features went for stories of the occupiers, especially as they found a few who were descendants of occupiers of the GPO in 1916. They homed in on Aubrey Robinson, a serious activist who did not seek the limelight, discovering that he was the son of ex-president Mary Robinson. As a leaderless movement, it discouraged grandstanders. There were a few, especially as numbers thinned, who strutted their stuff for media attention. One was named in two newspapers as ‘the leader’, although he was far from that, even allowing for the fact that there did emerge informal leadership in this formally leaderless movement.

The media coverage, although relatively benign, was not in proportion to what the occupation deserved, especially in the early weeks when there was so much activity at ODS. In contrast, the presidential election, which did not deal with any of the real issues facing us, was given saturation coverage. Still RTÉ, TV3 and Al Jazeera broadcast from the site, as well as reporting it and having participants on studio panels. Many of the newspaper features went for stories of the occupiers, especially as they found a few who were descendants of occupiers of the GPO in 1916. They homed in on Aubrey Robinson, a serious activist who did not seek the limelight, discovering that he was the son of ex-president Mary Robinson. As a leaderless movement, it discouraged grandstanders. There were a few, especially as numbers thinned, who strutted their stuff for media attention. One was named in two newspapers as ‘the leader’, although he was far from that, even allowing for the fact that there did emerge informal leadership in this formally leaderless movement.

We did not rely on mainstream media alone. The be-your-own-media approach included website, social networking and video production. Indymedia, Dublin Community TV and Trade Union TV recorded much of the occupation, as did filmmaker Donnacha Ó Briain, whose documentary we have yet to see. There were also blogs, the most consistent being David Johnson’s Booming Back, giving an upbeat look at ODS without ignoring its more downbeat moments. I did constant diaristic updates on Facebook.

The Garda Síochána have adopted a low key presence in relation to ODS. They were visibly co-operative, even helpful, at the site and on marches. On one march, I saw a garda miming ‘We are the 99%’, whether consciously or not. What the modus operandi of the special branch has been in relation to it, I do not know. The government has not addressed the issue of the occupations or made any move to evict them. The gardaí did indicate that the Central Bank might seek an injunction, especially after more solid wooden structures were erected. On one occasion, ODSers were all day in the courts on standby, listening to cases on fishing and liposuction all day, just in case.

We watched while so many encampments in the US were evicted. I took particular notice of those in Wall Street and Philadelphia. Without any dramatic scenes of police moving in with truncheons and pepper spray, we began to feel a loss of our encampment too. It was less dramatic, but more difficult in its way. The camp versus movement dynamic became increasingly unhealthy, playing out in such a way that the movement virtually disappeared, leaving only a camp, more and more preoccupied with its own existence and lashing out at those who disappeared, even though they were the ones who had driven so many people away.

This raised questions of the organisational mode of these occupations, especially this one. The fact that it was open to all meant that it was open to ignorant, addicted, deranged, vainglorious, poisonous people and perhaps agents of hostile forces. Even a few neo-nazis camped for a while, arguing that they were the 99%. Yet there was increasing hostility to trade unions, to the left, to intellectuals. The negative attitudes and activities of a minority threatened to overwhelm the positive forces set in motion, because the come-all-ye approach, combined with the use of the blocking mechanism and the dominance of the camp over the movement, made it possible for these negative elements to prevail. It was not democracy. It was dictatorship of a minority. It did not prefigure any society we wanted to see.

Numbers turning up for assemblies and marches declined to the point where they became unviable. The march on 10 December gathered only 20 people. I was one of them. I then spoke against marching. Others wanted to march, so I stepped aside, dissenting without blocking. I arrived at ODS later, where there was music playing, attracting passing interest, but I recognised few people I knew from assemblies, talks or previous marches.

Those were still were serious and committed political activists coming and going, even camping, as well as the ‘heroes of the revolution’ living in their bubble. Both of these were threatened by a criminal element who threatened to shoot or stab the people or burn the place. There were problems with theft, drug dealing and an array of violent behaviour. One admired community activist was thrown out.

Tensions between the media team and the campers reached breaking point and some of the most hard-working members of working groups disappeared. We suspended OU talks on 9 December, but met to plan our approach for phase two. Every time I went to ODS in December, there were fewer people there. Even on milder days with many people passing by, there was no one on the street to interact with anyone who wanted to make contact. I went through the barriers on several occasions to find about six people, most of whom I had never seen, who did not seem interested in talking to me. I came back on Christmas eve with books I had bought for the library wrapped as Christmas presents.

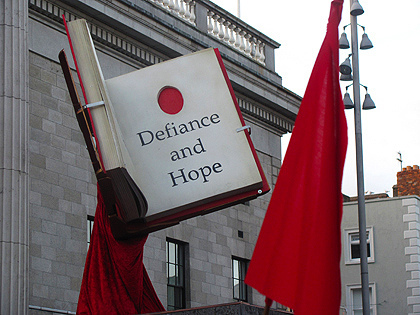

There were some good intervals in December. One was the Spectacle of Defiance and Hope on 3 December. Organised for a second year by a coalition of community groups, the ODS assembly made the decision to liaise with it with no concerns, objections or blocks. It was colourful, creative and communal. The theme song of the day was Liam Weldon’s Dark Horse on the Wind and the words ‘Arise, Arise, Arise’ echoed through the streets. It started at City Hall with a dark horse ridden by a person in a long flowing black cape and hood, the grim reaper, and ended with a phoenix rising. It stopped at ODS, which joined the march there, just ahead of the phoenix. In early December, there were also protests against the government budget and ODS was on the streets outside Dáil Eireann. There were issues between the different groups, but not the fault of ODS on this occasion. There were a number of direct actions in banks and government offices, which were constructive and benignly received by those working in these places.

There was one direct action, though, which was seen as a symptom of degeneration. A group went to Áras an Uachtaráin to invite Michael D Higgins, the newly elected president, to come to ODS for a cup of tea. They circulated a 14-minute video on the web, which was painful to watch. It was, according to one ODS supporter on Facebook, familiar with the genre of children’s tv, ‘a cross between The Wicker Man and Spongebob Squarepants‘, and showed ODS disintegrating into political incoherence. There was also a feature on national radio around this time, in which campers indulged in incoherent and deluded talk of revolution. This same commentator, in his blog Cunning Hired Knaves, put forward a constructive critique of ODS, the most devastating aspect of which was a list of developments occurring in Ireland during the period of the occupation, and their relation to the demands, where the situation of the country had deteriorated and we had been further disempowered. ODS had not addressed or acted upon any of these. This was a criticism of us all. A number of people engaged with it in a healthy manner, whereas others responded by pointing out that he wasn’t camping, that he was pissing all over their world, that with such friends who needed enemies.

Much of the controversy flared on Facebook for various reasons, including the decline of assemblies. I initiated some of the most acrimonious exchanges, as I believed that some things needed to be said in order to define the situation to decide how to move on from it. I wrote: ‘First the problem was the SWP. Then it was DCTU. Or even, more generally, the left and the trade unions. Then it was the media team. Now it is the “intellectual elite” (defined as people who read books, write blogs, organise talks, articulate criticism). If only it could be just the “heroes of the revolution” and “the people” without all these “parasites” in the way. So where are the people?’ This generated many comments.

The OU working group intended to organise a day of reflection for ODS in the new year. However, too many people in the movement, particularly in the working groups, had gone away and didn’t want to go on with some of those remaining. The media team took the initiative of convening the dissident majority, the reality check wing of the occupy movement. It was back again to Seomra Spraoi, where we gathered in January, to discuss forming a new occupy group and to make plans for bringing the positive energies unleashed by this movement into phase two. It would focus on organising, not camping. It would open out to relations with other groups, such as trade unions. It would initially abandon the open call to all characterising phase one, starting with a circle of people who came to know and trust each other. In response, we were denounced as an elite, as splitters, as parents who threw their children into a fire.

However, some in ODS want to address the real issues. The new group will be complementary to ODS, rather than in opposition to it, and some will be in both groups. On 15 January, ODS issued a statement marking the 100 days of its existence, admitting (although not specifying) its mistakes and expressing its determination to continue.

Globally this is a genuine grassroots manifestation. It is the cutting edge movement of our time. It has unleashed a tide of powerful resistance to global structures of power. Ireland is in the firing of the forces this movement has set out to resist and needs to be part of it. The situation is fluid. The new year got off to a flying start with an occupation of a factory in Cork, a shop in Dublin and a bank in Belfast. An empty office building in Cork has been occupied and transformed into a community resource centre. There will be more of this, especially in Dublin, where plans are brewing, nearly boiling. Occupy University will continue in multiple locations: in universities, in occupied buildings, on the streets. The Occupy movement has brought new focus, new energy, new fluidity into the convergence of forces confronting a powerful plutocracy.

2011 was the year when the voices of the 99% spoke truth to the power of the 1%. We still have not convinced enough of the 99% to resist and the 1% still rule. Nevertheless the class struggle being waged from above has begun to be met with class struggle from below. This will intensify in 2012. {jathumbnailoff}

Originally published on Irish Left Review.

Images: David Johnson, Aoife Giles, lusciousblopster, photojonathan, infomatique, Eadaoin O'Sullivan. All images licensed under Creative Commons by/by-nc-sa/by-sa except Image 6, (c) Aoife Giles.