The politics of the ongoing bailout

One of the things you might notice, with regard to the Stability Treaty referendum campaign in Ireland, is the way the issue is presented as a purely Irish affair.

To a certain degree this is an outcome of the nature of a constitutional referendum: it falls on those people living in Ireland who live in the Republic and who fall under the category of Irish citizen to vote on whether or not the treaty should be ratified. Thus, however scrupulous the rules regarding media coverage in terms of equal airtime given to proponents of either side of the argument, there are certain political considerations systematically left out.

For one: does the opinion of those people living in Ireland who do not hold the status of Irish citizen count for anything? In terms of how the referendum is presented to us, and in keeping with the overwhelming tendency in Irish political discourse, it does not, even though many of these people are likely to be those worst affected by the regime established by the Treaty.

Two, the Irish citizens defined as being able to choose between the two options are impelled to weigh up their considerations, through the media coverage, in terms of what is ‘best for Ireland’, or what is ‘best for the State’, with all the polymorphous vagueness that that term entails in the context of Irish political discourse. It is worth bearing in mind that the underpinning logic here is largely the same logic formalised and enforced by the EU Economic governance “Six-Pack” – the standardisation of rules on deficits, public debt, and public expenditure and so on, enforced from above by the European Commission - which the Stability Treaty seeks to constitutionalise. Whilst these rules give the impression of a collaborative undertaking, in reality they amount to a race to the bottom, in terms of wages and labour rights and concessions afforded to speculative investment; a downward convergence based on competition between states, under the primacy of finance capital, not solidarity across the different peoples who live within the borders of the European Union. The question of ‘what is best for Ireland’, then, assumes all this as naturally existing fact.

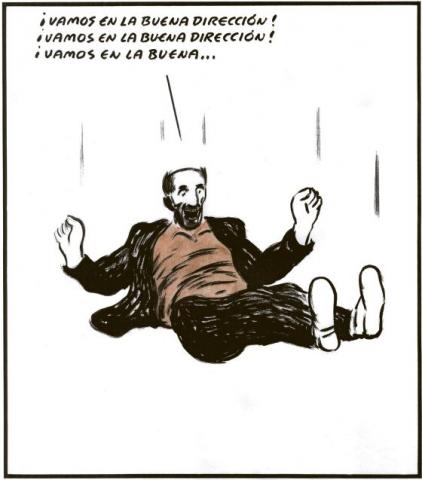

Three, following on from the previous consideration, the question of ‘what is best for Ireland’ as it is presented effaces any question of class antagonisms within Ireland, and places in its stead the notion of the ‘national interest’. So, for instance, when David Begg – hardly a fire-breathing radical - announced to the Labour Party conference that European solidarity was a defunct concept since places like Greece and Ireland had now become living laboratories for neoliberal experimentation, the response of Labour Party leader Eamon Gilmore, when questioned about this on an RTÉ current affairs programme, was to say that the referendum was not about the interests of any particular group, but the national interest. At least Gilmore is consistent: recall his campaign phrase of ‘One Ireland – of employer and employee’. Moreover, Labour’s referendum campaign has produced posters with an image of a resplendent tri-colour dominating the poster and the word ‘Labour’ as a miserable afterthought on the bottom right hand side.

You do not need to be a semiotician to work out what is being said with this image. Thus one of the effects of the referendum campaign has been the mobilisation of nationalist sentiment so as to win consent for neoliberal punishment. This right-wing nationalist lurch in the Irish context is mirrored elsewhere in Europe. As Costas Douzinas notes of Greece in the Guardian, ‘Part of this picture – its most worrying aspect – is the rush to the right by mainstream politicians who, imitating Sarkozy, compete to display their nationalist credentials.’ This form of campaigning will have a grievous effect on the political atmosphere in Ireland: the erosion of labour rights set in train by the Treaty regime will be replaced by claims laid to entitlements as Irish ‘citizens’ to the exclusion of such entitlements for other people – whether guaranteed by political, social or labour rights. Witness, for example, the recent report in the Irish Examiner, where ‘Southern regional president of the SVP Brendan Dempsey said he believes there is an unwritten policy to urge homeless EU migrant workers to go back to their homelands’. The scene is set for the punitive character of social welfare policies to be intensified, and along with it, a more generalised racist backlash.

You do not need to be a semiotician to work out what is being said with this image. Thus one of the effects of the referendum campaign has been the mobilisation of nationalist sentiment so as to win consent for neoliberal punishment. This right-wing nationalist lurch in the Irish context is mirrored elsewhere in Europe. As Costas Douzinas notes of Greece in the Guardian, ‘Part of this picture – its most worrying aspect – is the rush to the right by mainstream politicians who, imitating Sarkozy, compete to display their nationalist credentials.’ This form of campaigning will have a grievous effect on the political atmosphere in Ireland: the erosion of labour rights set in train by the Treaty regime will be replaced by claims laid to entitlements as Irish ‘citizens’ to the exclusion of such entitlements for other people – whether guaranteed by political, social or labour rights. Witness, for example, the recent report in the Irish Examiner, where ‘Southern regional president of the SVP Brendan Dempsey said he believes there is an unwritten policy to urge homeless EU migrant workers to go back to their homelands’. The scene is set for the punitive character of social welfare policies to be intensified, and along with it, a more generalised racist backlash.

Four, general awareness of life in other European countries is kept to a minimum by the way European politics is mediated. People are not inclined to care much about what goes on – in terms of people’s daily lives, their history, their culture - even in those countries geographically closer to Ireland. Whenever European politics is reported, it is nearly always in terms of crude caricature, and through the prism of the challenges faced by European leaders – the counterparts of the Irish ones - in disregarding the needs and desires of the people they are supposed to represent, or, as the media puts it, ‘the hard work of convincing their electorates’. This is in spite of the fact that there are plenty of people originally from other European countries living in Ireland whose lives form part of the fabric of Irish society. Thus there is practically zero importance afforded to the consideration of what it might mean to think about voting in the referendum on account of a common bond with people living in other European countries. If anything, it is actively discouraged.

Five, the referendum campaign, I fear, obscures rather than casts light on what is actually going on in Europe at the moment. Certainly it naturalises certain things that might otherwise be open to political discussion as faits accomplis: the ramifications of the six pack, for instance, were never subjected to any scrutiny whatsoever in terms of their impact on life for the majority of people in Ireland, or whether such things were desirable. And the debate over whether it is appropriate to bind parliaments to meet a particular set of GDP related targets has obscured entirely the fact that GDP, as an economic measure, largely serves the business class, in that it excludes all manner of productive activities (for instance, raising children, domestic work) from consideration with regard to economic policy and includes all manner of unproductive, even destructive ones, for instance, those activities associated with asset price speculation. But most importantly, I feel, it suspends any sense that what is happening right now, while this campaign is underway, is an enormously destructive phase of European capitalism in which all manner of anti-democratic measures are being introduced and rights are curtailed, under the guises of ‘reform’, and ‘stability’.

As the translated article below, by Boaventura de Sousa Santos, writing from the point of view of Portugal, points out, time is of the essence in activating resistance to the ‘post-socialdemocratic order’ being imposed. A ‘No’ vote would be an essential component of such a resistance, but it has to come with a widening of the political imagination, an awareness of the need for new alliances to be formed, and consciousness of what he names as PREC – the politics of the ongoing bailout, which I think is the frame in which we should perceive the narrowing of the referendum debate down to the question of ‘Where are we going to get the money from?’

The critical sociology of the catastrophe

There is no European consensus about the fiscal policies or the austerity programmes underway. What there is, however, is a consensus of the right-wing and an ongoing inability of the European lefts to present a credible alternative at the level of each country. As long as this goes on, time is the most uncertain and the most decisive factor in the resolution of the European crisis.

The more it passes, the more we will see a consolidation of the new post-socialdemocratic order thought out long before the crisis and which the right-wing now wants to impose and consolidate over the coming decades. The new order is a heaven for finance capital, a purgatory (this time without an ecclesial blessing) for productive capital and a hell for the immense majority of citizens, a catastrophe for life expectations that until now appeared reasonable and deserved. The catastrophe is being administered in supposedly homeopathic doses so that the paralysis of alternatives lasts more time (today, a cutback, tomorrow a rise in the price of water and energy, the day after, the closure of a service). What can be done to shorten this time?

1. Know where we are headed. The end of convergence is underway. The plan A of the politics of the ongoing bailout (PREC) [In the translated Spanish version ‘política de rescate en curso’] consists of creating the conditions so that the countries in difficulty return to the ‘normality of the markets’. This is only possible at the cost of more wage reductions, more cuts to public spending and the subjection of these countries to a non-negotiable discipline that compromises and empties out their sovereignty. Thus there is a consolidation of a duality between developed and less developed countries in Europe’s interior. Portugal, Greece, Ireland and (perhaps?) Spain will be the Mexico of Europe. If we do not want this Europe, it is urgent to struggle for this to come to an end.

2. PREC can only produce two results: more PREC or expulsion from the euro. News reports and blogs on financial funds predict (they know, because they are the ones who realise the predictions) that, as with Greece, the first bailout is followed by a second one with greater restrictions, more austerity, and a certain restructuring of creditor debt. This means that Portugal could be under guardianship for several more years (until 2018?) and, should this be the case, an entire generation will have lived under a colonial regime disguised as democracy, but controlled, in practice, by a regal firm, Goldman Sachs. If, however, plan A does not work, there is plan B: expulsion from the euro or a solution that produces the same effect. This is something that is already being spoken of as regards Greece. If plan A is devastating for our aspirations as a European country, expulsion from the euro would be no less so due to the conditions in which it would occur, after PREC has destroyed our economic base (which until a little while ago gave indications of a qualitative change in product specialisation), after it has shredded our wealth, our savings, our gold. We might make allowances for the Socialist Party feeling prisoner of PREC 1, but it is inadmissible that it should not declare itself against any PREC 2 or 3. This is its opportunity to make a break from spurious inheritances and start building an alternative.

3. Disobedience within the euro. It seems incredible that, in spite of all this, a non-catastrophic solution for our country has to be found at a European level. But it must be so, even if two very demanding conditions are necessary for it. The first is political actors who explore all the cracks in the system. General international law and the vast majority of international treaties hold derogation clauses in the event of national emergency. This derogation can involve the temporary control of capital and imports, as well as a moratorium on the servicing of debts. Can this disobedience on the part of a small country be punished with immediate expulsion? All this depends on the alliances that are forged on the way. Three things are for sure: whoever does the expelling will still run big risks; someone will have to disobey and someone will have to be the first; it is unthinkable that the Paris-Berlin axis should continue as the only one in the European Union and that it should not be possible to build alliances with other countries, among them, tomorrow, with France itself.

The second condition has to do with the European political system. The approaches that involve the whole of Europe must be formulated at a political level that gives them credibility. As has been seen, this level cannot be the national one. We must, therefore, re-found the European political system with the creation of a single European electoral constituency and transnational lists from which new leaders of a truly democratic Europe emerge. Inside or outside the euro, by choice or by imposition, there will be disobedience; the problem is knowing what level of disaster will be reached.

{jathumbnailoff}