Welcome to dystopia

The media campaign against Fianna Fáil in government amounted to a political movement of dissent, rather than an objective critique of policy, writes Desmond Fennell.

In a recent article for the Irish Times, "Searching for the source of perpetual passivity", Dan O'Brien searched for an explanation for "the very limited political and societal reaction to the country's economic crisis". Contrasting what he saw as the mild public reaction in Ireland to that which led in Iceland to "the toppling of a government" and in Greece to "violent demonstrations", he found the explanation for the Irish difference in the Republic's "weak infrastructure of dissent".

Leaving aside that the economic crises in Iceland and Greece were considerably more extreme than in Ireland, I believe that future Irish historians – with the benefits of distance and uninvolvement - will take a different view than Mr O'Brien of the reaction in the Republic. They will see and recount that it was strong; that in accordance with Irish culture it took a predominantly verbal form; that its "infrastructure of dissent" was provided by a combination of the Dublin mass media with the published feedback from thousands of citizens; and that this combined reaction to economic mismanagement "toppled", as in Iceland, the incumbent government.

Delving into the archives of the Dublin newspapers, television and radio stations, these future historians will notice that from early 2009 to a month before the election, the media pluralism in matters political, proper to a liberal democracy, disappeared. All Dublin media organs, while giving voice to the government/Fianna Fáil, dissented from it and wished openly for its demise. All of them, editorially or through their regular contributors, were diligent in blaming Fianna Fáil for the recession and finding fault with the government's would-be remedies. No media organ favoured or supported the government/Fianna Fáil.

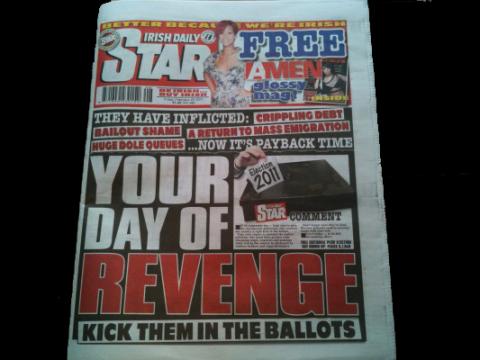

Sledgehammer words such as "outrageous", "scandalous", "irresponsible", "catastrophic" resounded repeatedly in the media discourse. The dissent extended to the Republic itself. To the amazement of foreigners among us, the Republic was depicted as a dystopia, a "country where everything is bad", and the government as the cause of this. "A "mess" and a "broken system" became cliché descriptions. The publication of reports on clerical child abuse was used to reinforce the language of apocalypse: church had failed us along with state, Irish Catholicism joined the Republic on the scrap-heap.

Dissent even from Irishness entered sections of the Dublin media, dumbfounding foreigners. Fianna Fáil was represented as embodying the quintessentially native element in Irish politics, hence its alleged vices were typically Irish vices. Ergo, the Irish way of conducting public life had corrupted the Republic and must be eradicated by the eradication of Fianna Fáil. Historians with a linguistic bent will note how often in these years in the Dublin media the adjective "Irish" had a pejorative connotation.

What to do? The logic flowing from the awfulness of what the government/Fianna Fáil had done was that the Republic must be remade from scratch: Constitution, voting system, health system, Oireachtas. Editors invited and encouraged articles on "renewing the Republic" from the bottom up and many such articles were published.

But as I indicated above, the Dublin media's language was only the bulldozing and instigating vanguard of the "infrastructure of dissent". Equally part of this ultimately successful operation was the media's eliciting and publication of support for their account and diagnosis from the general public. All media laid the ground for such support by stating repeatedly that "people are angry", that distress was widespread and that forced emigration was rising massively. Television talk shows ensured that people with "hard-luck stories" to tell would be present in the studio audience and available to be called on to tell their stories. Television and radio reporters visiting towns around the Republic made sure to find such people and to make their voices predominate in the broadcast reports. Letters-to-the-editor that were published, as well as phone calls, text messages and tweets to broadcast programmes that were either, as the case might be, transmitted directly or read aloud, were predominantly supportive of the media's radical dissent. This publication of what appeared to be mass support for the media's message made opposition to government/Fianna Fáil seem the norm of the nation, thereby doubling its force.

Those future historians will have good ground for identifying the widely supported Dublin media operation of 2009-10 as a political movement of fundamental dissent – the Irish equivalent of protesters on the streets in Reykjavik or Athens – rather than a case of mass media operating in a normal manner to report and reflect realities. The historians, having also consulted other sources about life in the Republic in 2009-10, will have found these in fundamental disaccord with the Dublin-media version. They will have learned from them that the Republic, far from being a dystopia, was, for example, still one of the world's richest countries and still ranked where it had ranked in 2005 in the United Nations' Human Development Index, namely, in fifth place (Iceland having slipped ten places to 17th.)

In certain respects, they will note, the media got it right because some solid facts were to needed give some appearance of justification to their comprehensive dissent. Serious bank debt and state debt did indeed cast a shadow over the future. And as in any recession following a construction boom, unemployment and taxes had increased, and more householders than previously were defaulting on their mortgages. But official statistics showed that 86 per cent of employable persons were in gainful employment, many people were buying new cars, most restaurants remained open and busy, and agriculture and manufacturing were prospering, as exports increased. A new report of the World Bank on Doing Business ranked Ireland ninth out of 183 countries as a good place for doing just that.

In the final analysis, it will be the hysterical myth-making of the Dublin mass media about Ireland as a ruined and broken nation that will guide our future historians to identify this combination of writings and broadcasts by journalists with the written and spoken feedback of ordinary citizens as the Irish equivalent of raucous street demonstrations elsewhere during the recession of 2008-10.

Desmond Fennell's books and essays are available here.