The high-tax, low-tax conundrum

Irish tax rates are average, but we fall down badly on social insurance. We need a revolution in insuring society. By Michael Taft.

It is commonly asserted by progressives that Ireland is a ‘low-tax’ regime. Therefore, goes the argument, we should focus on tax increases rather than spending cuts – if we aspire to European level of public services and investment. This doesn’t tell the full story, though. Yes, government revenue is low by European standards. However, Ireland is an average taxed economy. The problem is that we are a woefully low-insured economy. This should alert us to more sophisticated strategies in the run-up to this and subsequent budgets. Let’s take a quick survey and see what lessons we might draw.

Overview

In any comparison we come to the question of the benchmark. Some use GDP, whereas others prefer GNP. This debate can become almost scholastic and I don’t propose to settle it here. So let’s use another benchmark – tax revenue per person employed. After all, income tax, PRSI, etc. is a function of how much those at work pay in taxes. I’m not suggesting it is a superior measurement; just a different perspective. We will use Eurostat’s Trends in Taxation, which takes us up to 2010. We will further use the EU-12 excluding Luxembourg, Greece and Portugal. The small duchy produces outlier results as it contains a significant number of non-resident workers while the latter two are extremely poor in comparison with other EU-15 countries.

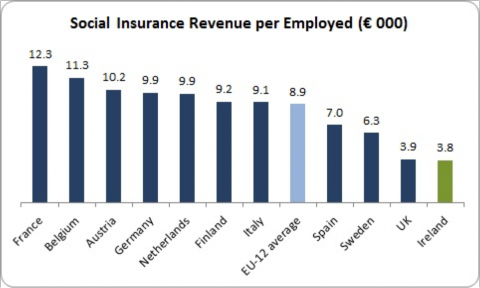

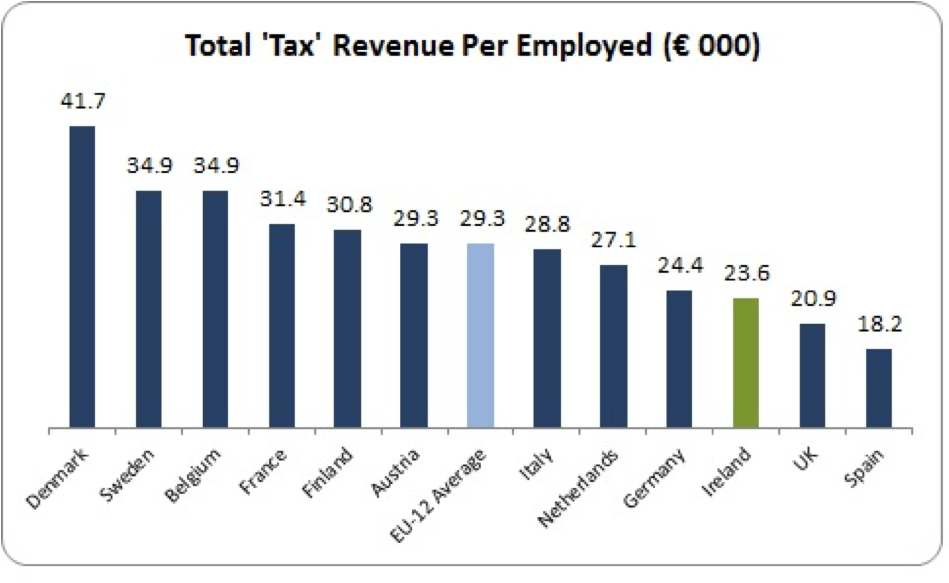

Overall, government tax and social insurance revenue is well below the EU core-average.

Ireland would have to increase tax/social insurance revenue by 24% in 2010 – or €10.7 billion – to reach the average of the other countries. Clearly this gives strong evidence for the ‘low-tax’ argument. However, from here on in it gets more complex.

Ireland would have to increase tax/social insurance revenue by 24% in 2010 – or €10.7 billion – to reach the average of the other countries. Clearly this gives strong evidence for the ‘low-tax’ argument. However, from here on in it gets more complex.

Main taxes

Looking at the three main taxes – income tax, corporate tax and indirect taxes (VAT, excise, etc.) – we find that Ireland is actually an average-taxed country.

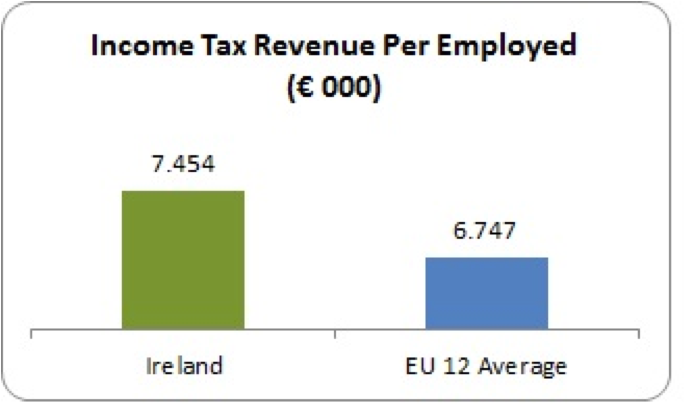

(a) Income tax

Even more surprising is that Irish income tax revenue per employed is higher than the EU-12 average – 9.5% higher.

There are a number of caveats here. First, while the Eurostat data shows lower Irish tax revenue, that’s because they assume that the Health Contribution Levy was part of the social insurance system. However, it wasn’t – it was collected as part of the PRSI system but it was paid into the Exchequer (more specifically, the Department of Health), not the social insurance fund. I have adjusted for this.

There are a number of caveats here. First, while the Eurostat data shows lower Irish tax revenue, that’s because they assume that the Health Contribution Levy was part of the social insurance system. However, it wasn’t – it was collected as part of the PRSI system but it was paid into the Exchequer (more specifically, the Department of Health), not the social insurance fund. I have adjusted for this.

In addition, I have excluded Denmark, which doesn’t have a social insurance system (and, so, has a substantially higher level of income tax revenue) and Sweden for similar reasons, as the data doesn’t show employee PRSI revenue.

So, for income tax, while there may be distributional issues, Irish income tax is more than adequate in comparison with other EU countries.

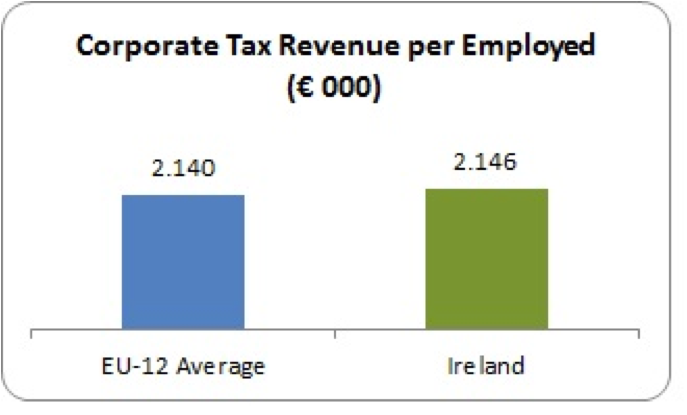

(b) Corporation tax

Irish corporate tax revenue is also average.

Again, this requires some explanation. The reason Irish tax revenue from corporations is higher than its ultra-low tax rate might suggest, is that we are actually taxing profits created in other countries which have been ‘imported’ here via transfer pricing. This more than flatters the Irish data. If we could break down data for tax on profits actually produced here, we would be well down the league. However, for the purposes of revenue, Ireland lives well enough on its ‘tax-flexible’ (some might say ‘tax-haven’) arrangements.

Again, this requires some explanation. The reason Irish tax revenue from corporations is higher than its ultra-low tax rate might suggest, is that we are actually taxing profits created in other countries which have been ‘imported’ here via transfer pricing. This more than flatters the Irish data. If we could break down data for tax on profits actually produced here, we would be well down the league. However, for the purposes of revenue, Ireland lives well enough on its ‘tax-flexible’ (some might say ‘tax-haven’) arrangements.

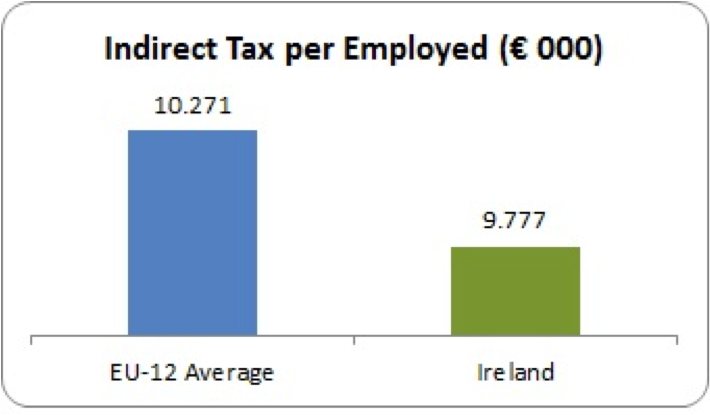

(c) Indirect taxes

Again, with indirect taxes (VAT, excise, etc.), Ireland is close to the average.

Again, with indirect taxes (VAT, excise, etc.), Ireland is close to the average.

Irish indirect taxation would have to rise by approximately 5% to reach the average of the other EU countries. The increase in VAT in the last budget will have brought us closer to the EU average, though the continuing fall in consumer spending will probably mean we are still slightly below average this year.

So, if Ireland – whatever the caveats – is broadly average in terms of the main taxes, why does it fall down so badly when compared with the total revenue of other countries?

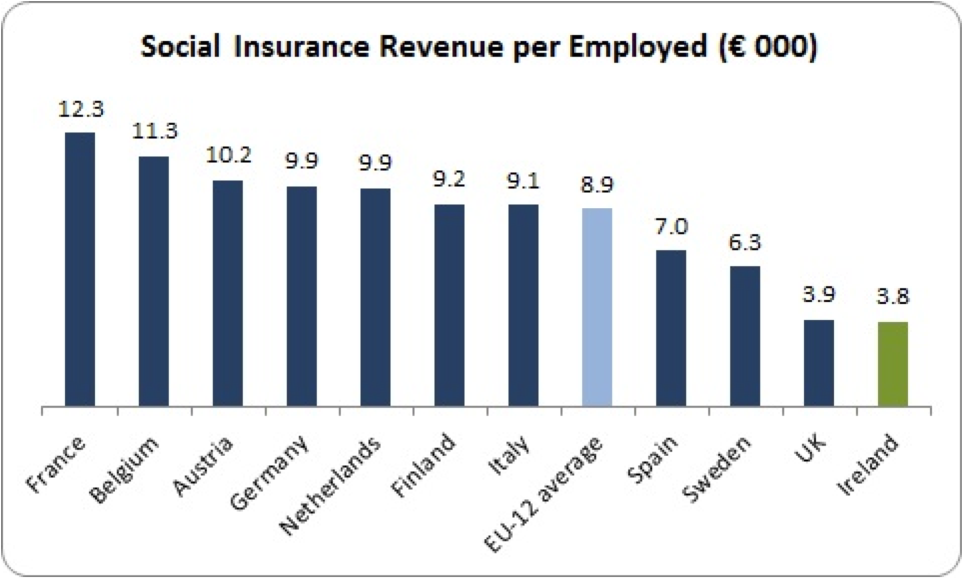

Social insurance

By any standard, Ireland has an anaemic social insurance system. We don’t have a universal health system or income-related benefits (unemployment, disability, pension, etc.). Our degraded level of public services and social protection is directly related to our low levels of social insurance.

We would have to more than double (132%) social insurance revenue just to reach the average of other EU core countries. We’d have to treble revenue to reach French levels. This gap, were it closed, would bring Ireland's total tax/social insurance system up to EU averages. Below we go through the main elements of the social insurance system.

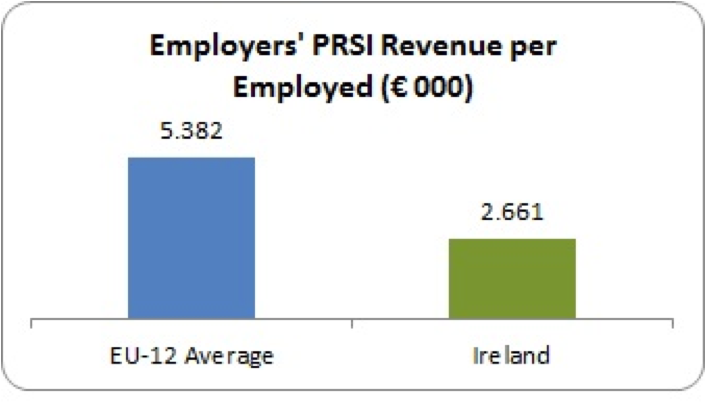

(a) Employers’ social insurance

Employers not only benefit from ultra-low corporate tax rates, they also benefit from extremely low PRSI rates. This results in a major gap between Irish and average EU levels.

We can better understand this when comparing basic employers’ social insurance rates:

We can better understand this when comparing basic employers’ social insurance rates:

- Ireland: 10.75%

- Austria: 21.6%

- Belgium 34.5%

- Finland: 23%

- France: 40% (on the first €100,000)

- Italy: 32% (on the first €90,000)

- Sweden: 31.4%

If anything, Ireland has been going backward – with the temporary reduction in the low-rate of employers’ PRSI last year.

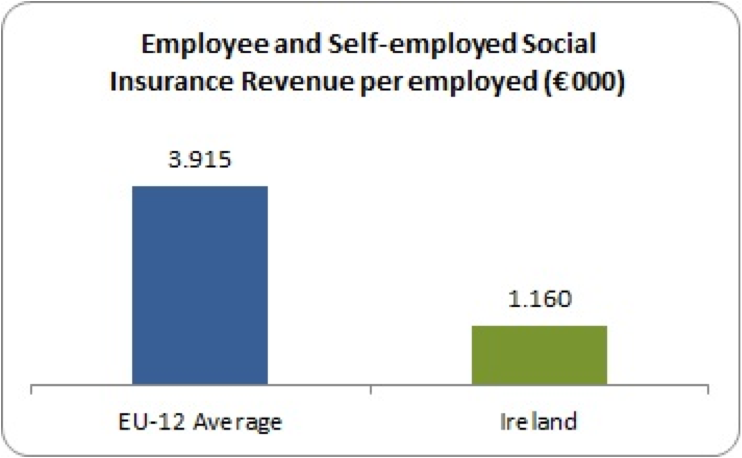

(b) Employee and self-employed PRSI

The gap between the EU-12 average and Ireland is even wider when we come to employee and self-employed social insurance.

We would have to more than treble PRSI contributions from the combined employee/self-employees just to reach the EU-12 average (in this calculation I have excluded Denmark and Sweden since they do not have PRSI contributions for employees and self-employed).

Again, we can see why when we consider the contribution rates. In most of the EU-12 countries, rates for employees are in double digits, though some have an earnings ceiling. This compares to our rate of 4%. Self-employed rates are pitifully low here in comparison.

* * *

Tax revenue is not the problem in terms of European comparisons. In the three main taxes – income tax, corporate tax and indirect tax – Ireland and the EU-12 average are approximately the same: €19,400 per Irish employed compared to €19,200 per the employed in other EU-12 countries. This is not to suggest there aren’t problems within the tax system; but in terms of revenue gathering, Ireland is average by EU standards.

Where we fall down is in social insurance. Were we to increase social insurance revenue to EU-12 averages, we’d raise €9.5 billion. But if we see social insurance as merely another mechanism to raise revenue, we can just increase taxes.

For social insurance is not a tax – it is the collective consumption of goods and services; public goods and services. It is (a) a contract – whereby an individual pays a percentage of income in return for access to income supports, health care, etc. (just like insurance); and (b) a social wage, whereby the employers’ contributions provide workers with access to goods and services (e.g. pay-related sickness benefit, unemployment benefit, pension, etc.).

For Ireland it would be a transformation in the way we deliver public services, social protection, and income support. What we currently pay for individually (GP care) we would, under an expanded social insurance system, pay for collectively – though social insurance contributions, thus receiving the GP care for free or at greatly subsidised rates.

Further, it would involve a significant transfer of expenditure from the Exchequer to the Social Insurance Fund. Prior to the recession, 35% of all government expenditure in the Eurozone came through social insurance funds; in Ireland, the figure was 11%. By transferring more expenditure functions (collective consumption) to social insurance, the pressure on Exchequer expenditure would be reduced.

There is nothing to suggest that this government intends to move in this direction. Even their universal health insurance proposal is not ‘social’ insurance as such – it is merely a mandatory requirement to purchase health insurance on the private market. There is no contribution from employees/self-employed through the PRSI system (which can be made progressive) or a contribution from employers.

All this can lead us to a new formulation: the issue isn’t whether we are high-taxed or low-taxed. After all, we are average-taxed. What we need is a revolution in insuring society.

Progressives can raise a new slogan: ‘A moderate-taxed, high-insured’ economy.

NOTE: For a comprehensive survey of the Irish tax system, please see the Community Platform's 'Paying Our Way'. {jathumbnailoff}